“Nature always wears the colors of the spirit.” — Ralph Waldo Emerson

Introduction

Nature is an ever-changing palette, and the pigments we derive from it reflect this dynamism. While synthetic dyes provide consistency, natural pigments are influenced by a host of environmental factors, making each batch unique. One of the most intriguing influences on natural pigments is the change of seasons. From the vibrancy of spring growth to the dormancy of winter, the seasons shape the color potential of plants, minerals, and even fungi used for pigments. Understanding these shifts allows artists and dyers to work in harmony with nature, yielding the most vibrant and lasting hues.

Seasonal Variations in Dye Plants

Spring and Early Summer: Fresh, Vibrant Tones

In spring, plants experience rapid growth, producing an abundance of chlorophyll and flavonoids. This results in bright greens, soft yellows, and delicate pinks. Some notable examples include:

- Japanese Indigo (Persicaria tinctoria):When extracting pigment, young leaves produce a vibrant blue, with shades varying from turquoise to deeper tones depending on processing conditions. Factors such as fermentation time, pH adjustments, and oxidation play a crucial role in determining the final pigment quality and intensity.

Variation in the intensity of indigo pigment extracted from leaves harvested in July versus first week of August. The highest intensity is achieved at the peak of summer.

- Coreopsis: When harvested early, coreopsis yields bright, clear yellow tones, which can deepen to more deeper hues as the season progresses.

Hues of coreopsis at different stages of harvest

- Dandelions: This resilient plant offers a full spectrum of color possibilities, with every part contributing to pigment or dy eextraction. The flowers yield warm yellows, the leaves can produce soft greens, and the roots may give subtle earthy tones. Seasonal shifts influence these hues.

Late Summer and Autumn: Richer, Deeper Hues

As plants mature, their pigment concentration changes. Many accumulate tannins, anthocyanins, and carotenoids, resulting in richer, more complex hues:

- Madder Root: As the plant matures, late-season harvests tend to produce richer, deeper reds due to an increase in alizarin content. The color intensity also depends on how long the roots have been allowed to mature.

- Goldenrod: As the plant matures, it produces a range of vibrant hues, from green-gold to rich yellow. The color variation depends on the plant’s growth stage, with some plants yielding a warm, deep gold as they reach full maturity.

- Acorns & Oak Galls: Rich in tannins, these autumn-harvested materials yield strong, earthy browns and nuanced greys. With time, the colors deepen, developing greater depth and complexity. They are ideal for ink-making, as tannin-based inks are inherently lightfast and become richer over time, unlike those derived from anthocyanin-based plants, which tend to fade.

Winter and Dormancy: Subtle, Muted Shades

In winter, plant growth slows, but that doesn’t mean color vanishes. Dormant plant materials and dried leaves can still be used creatively:

- Japanese Indigo: Dried leaves yield a different quality of blue compared to fresh dyeing.

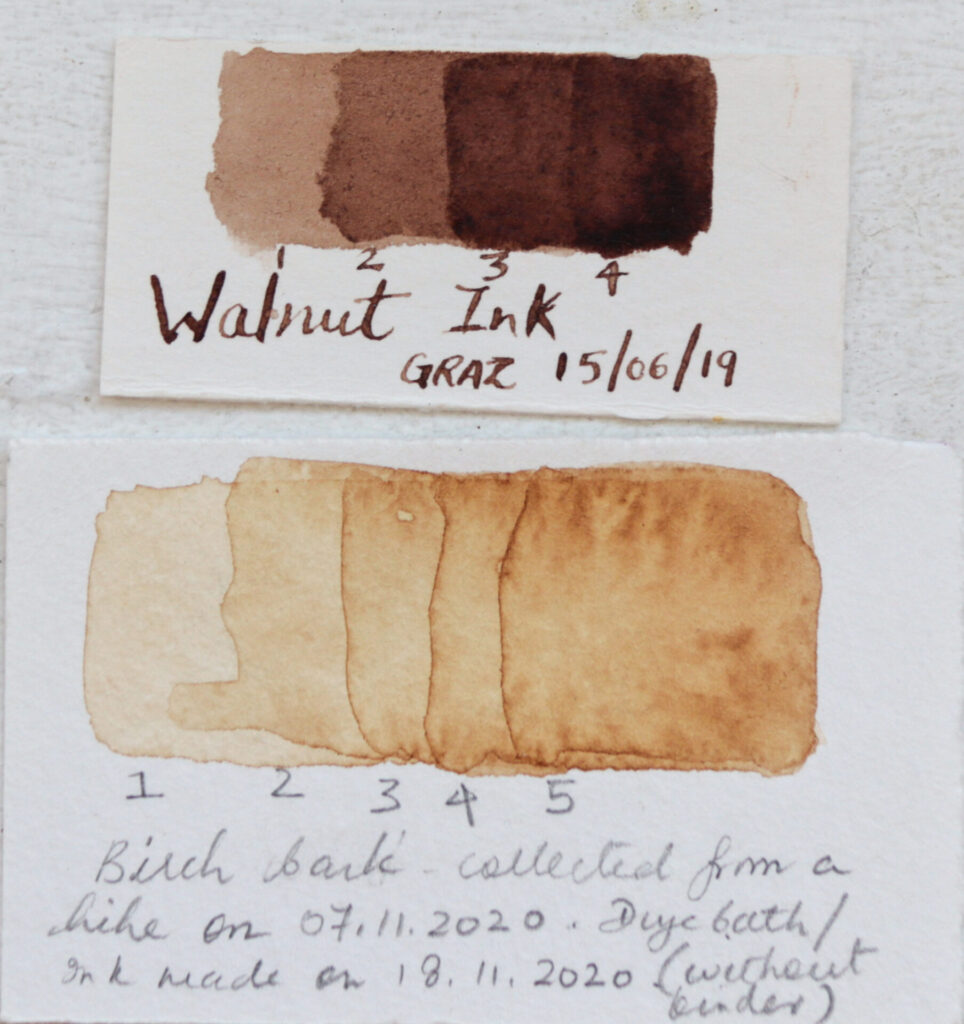

- Walnut Husks: A rich source of natural tannins, walnut husks produce deep, earthy browns that continue to develop even after falling. In ink-making, they create warm, durable browns that darken over time, offering greater permanence compared to anthocyanin-based inks, which are more prone to fading.

- Birch Bark: Depending on the species and extraction method, it can produce soft tans, warm pinks, or even deeper reddish-browns.

- Fungi & Lichen Pigments: Lichens and fungi can yield a range of colors, from purples and pinks to warm oranges, depending on the species, extraction method, and mordant used. However, I have only ever experimented once with lichen collected from a fallen branch. Due to their crucial role in the forest ecosystem, I choose not to forage for them, respecting their environmental importance.

Weather & Soil Influence on Color Outcomes

Rainfall vs. Drought: The Water Factor

- Abundant rain can dilute pigment concentration, producing softer hues.

- Drought conditions may lead to a higher accumulation of certain pigments, intensifying colors.

Soil pH & Mineral Content

- Alkaline soils (rich in calcium) often produce brighter, more vivid colors.

- Acidic soils tend to deepen and mute hues, sometimes shifting them entirely. For example, madder root grown in acidic soil yields more purples, while alkaline-rich soil enhances reds.

Temperature’s Role in Extraction & Fixation

Some plant pigments, such as those from safflower and annatto, are sensitive to temperature and can be effectively extracted at cooler temperatures. Safflower, for instance, produces two distinct pigments: a yellow pigment that is extracted in an alkaline solution and a red pigment that is more effectively extracted in an acidic solution. This means the pH of the dye bath plays a critical role in determining the color outcome, with no need for heat in the process. You can explore more about my experiments with safflower petals here.

Similarly, annatto yields its vibrant orange-yellow pigment without requiring heat, as high temperatures can degrade its color. On the other hand, anthocyanins found in plants like berries and red cabbage are heat-sensitive and retain their color better when processed at lower temperatures. Understanding the pH and temperature requirements of each plant allows for more control over the final hues, ensuring that you can harness the full potential of your natural dyes.

Annatto lake pigment converted into watercolor paint.

Experiments & Observations

Tracking Seasonal Variations: Cultivating my own dye plants has provided profound insights into the intricate relationship between climate and color. Even the subtlest shifts in environmental conditions can influence plant development, ultimately shaping the hues they yield. This phenomenon extends to the plants I occasionally forage—dandelions, acorns, goldenrod, and buddleja—where close observation reveals nuanced variations in dye and pigment outcomes in response to seasonal and climatic fluctuations.

Maintaining a dye journal allows for a systematic exploration of these variables, enabling a deeper understanding of plant-based colorants. Key practices include:

- Documenting harvest time, plant species, and environmental conditions with precision.

- Conducting comparative studies by testing the same plant across different seasons.

- Experimenting with soil amendments to analyze their impact on pigment expression.

Conclusion

Understanding the impact of seasonal changes on natural pigments allows artists to work more intuitively with their materials. Rather than seeing color shifts as inconsistencies, they become an invitation to deepen our connection with nature’s cycles. By embracing these variations, we create artwork that is not only beautiful but also a true reflection of the living world around us.

No Comments